A Life Reclaimed: Her Story & Ours

In the fall of 2016 we began to screen our first hour's rough cut to various audiences to get feedback and broaden the circle of interest in our work.

“Keller was, for me growing up, one of those almost fictional characters, and I think this was in part because I was never taught to think about her life within the context of a larger disabilities rights movement. Hers was instead a story of personal triumph over adversity that did not have any larger historical import. Needless to say, this differed dramatically from the way I was taught about, say, Rosa Parks, who seemed very much a real person in history to me, though she was no less historically remote than Keller. All to say that I was quite edified by what I saw of your film.” Chris Beha, novelist, former and editor Harper’s magazine

The Story of Her Life

Helen Keller became deaf and blind at the age of 19 months, after a high fever. She first met Anne Sullivan in 1887, at the age of seven. Sullivan was 20 years old and a graduate of the Perkins School for the Blind in Boston, valedictorian of her class. She arrived to work in the Kellers' Alabama home in the fall, and it took only three weeks for Helen to recognize that Anne was trying to communicate with her. Keller’s voracious thirst for words and knowledge began. Within a few months, Helen was writing sentences.

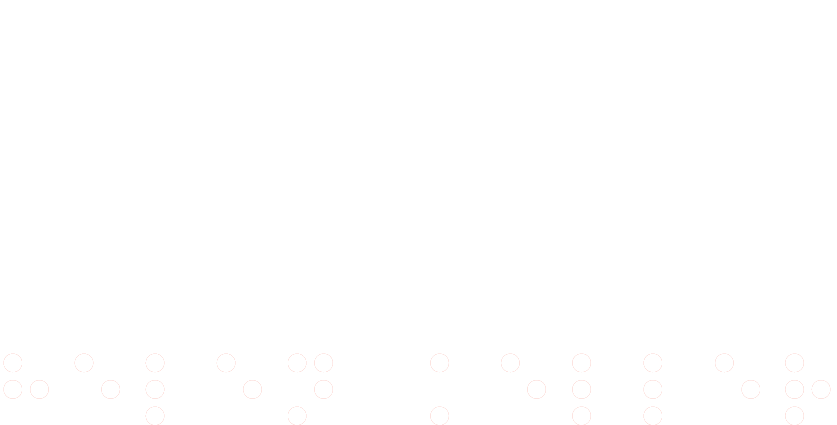

One year later, Anne took Helen to Boston. By then Helen was the subject of numerable newspaper stories that the Perkins School for the Blind helped distribute nationwide. Bostonians were delighted by Keller, her intelligence, her sweet nature, her fierce resolve to learn. Their amazement arose from the then nearly universal belief that disabled persons were less capable than able-bodied people – that a disability of any kind lowered capacity for all endeavors. Even as a child Keller disproved this deep-seated assumption.

Keller pursued her education relentlessly, graduating with honors from Radcliffe in 1904. Anne Sullivan accompanied her to class as interpreter. Volunteer tutors and friends also translated, and donors helped pay for living expenses, tuition and fees, brailled books, and travel. None of these accommodations were mandated at the time, and they often led to controversy. To help guarantee Keller's education could continue, her friend and admirer Mark Twain campaigned among his rich and powerful acquaintances to subscribe to a Helen Keller's education fund.

Keller went out into a sometimes hostile world that marveled at her accomplishments, but didn't always trust her. In her 20s she published a best seller, gave lectures, wrote opinion pieces, and joined the Socialist Party. Her critics questioned her competence to form her own political views. She served on the Massachusetts Commission for the Blind, and continually lobbied for employment and inclusive opportunities for all people. Her lifelong activism will likely surprise you.

“Women insist on their 'divine rights,' their 'inalienable rights.' There are no such things... rights are the things we get when we are strong enough to make good our claim to them." Helen Keller, N.Y. Call, 1913

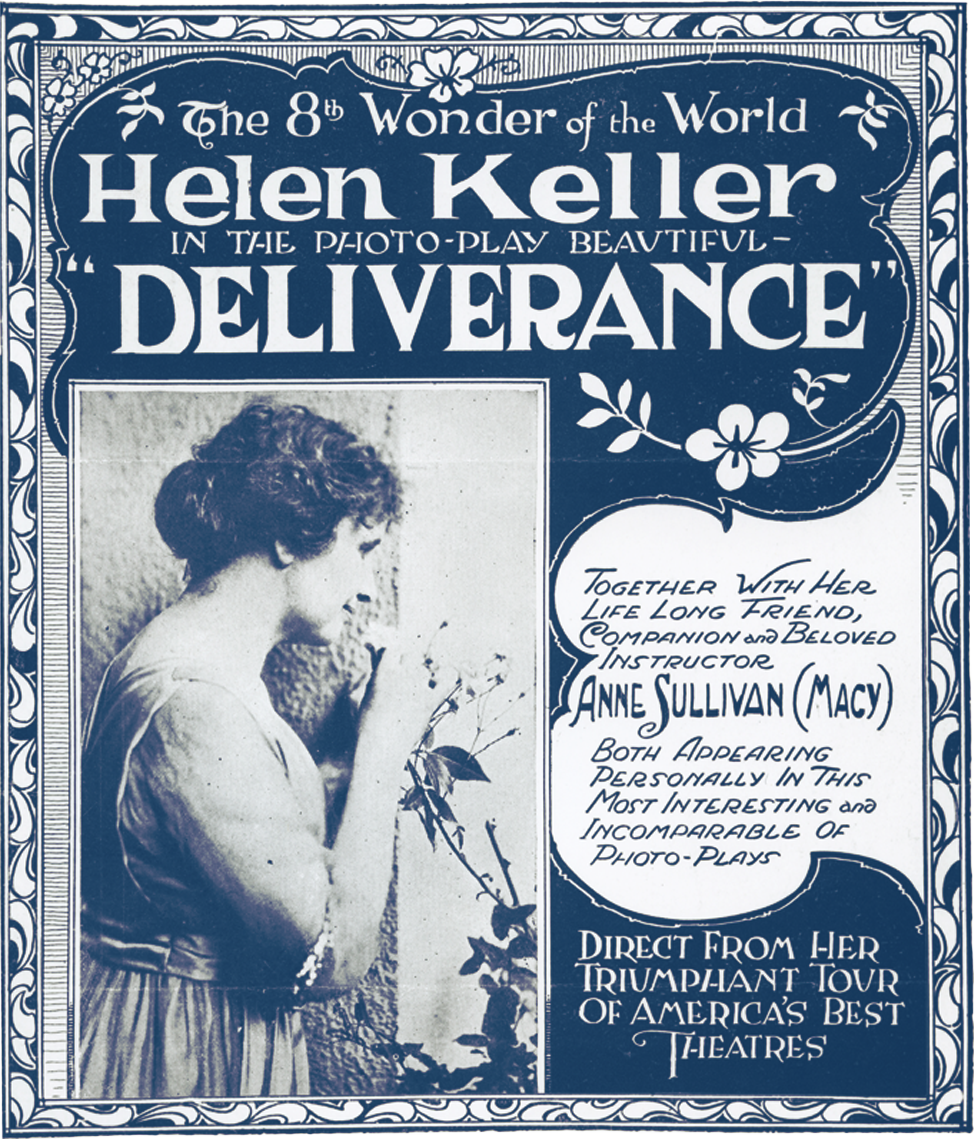

Keller would go on to write many books, hundreds of articles and essays for magazines and newspapers, and she would meet the public in lecture halls and theaters. Sometimes she spoke and wrote for social justice, sometimes as a professional fundraiser, sometimes as a lobbyist, sometimes as an entertainer. She went to Hollywood to film her life (Charlie Chaplin adored her), then performed as herself on Vaudeville. She worked and socialized with Alexander Graham Bell, Mark Twain, Eleanor and Franklin Roosevelt, even Martha Graham. She often lived in hotels, traveling thousands of miles on trains, boats, and planes at a time when almost nothing in the environment was accessible.

After WWII, Keller toured Japan, with the help of the US State Department and several non-profits. There she was instrumental in helping to raise funds and interest in new social-welfare legislation that became part of Japan’s post-war social contract. Keller was so successful there that throughout the 1950s she would be sent around the world as a good-will ambassador. Into her late 70s, she advocated around the globe for basic health care, education, and employment for people with disabilities and for women.